To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty, but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, kindness.

What we choose to emphasize in this complex history will determine our lives. If we see only the worst, it destroys our capacity to do something. If we remember those times and places—and there are so many—where people have behaved magnificently, this gives us the energy to act, and at least the possibility of sending this spinning top of a world in a different direction.

And if we do act, in however small a way, we don’t have to wait for some grand utopian future. The future is an infinite succession of presents, and to live now as we think human beings should live, in defiance of all that is bad around us, is itself a marvelous victory.

-Howard Zinn in his autobiography “You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train”

I like the name of Howard Zinn’s autobiography, “You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train.” We are all on a moving train, destination unknown. Source unknown, for that matter. We are born, we live, and we die in mystery. Neutrality is impossible, for even if we try to make our (supposedly) rational minds adopt neutrality, our very bodies take a stand, because they usually ache for self-preservation, for life, no matter what.

So, if we can’t be totally neutral, why not choose? Why not choose to live “in defiance of all that is bad around us”? Why not choose hope?

Now, I know all of us have times in life when the trap door opens beneath our feet and we plummet into free fall. People do lose hope for sure. We face chasms carved by loss, despair unleashed by terrible diagnoses, troubled relationships, or unspeakable living conditions. There are parts of the world — Gaza comes to mind, Congo with the resurgence of monkeypox comes to mind, Ukraine comes to mind, any place where children go to sleep hungry and afraid comes to mind — where nothing but devastation and destruction seems evident. Hope is pretty hard to capture in such places and situations. So, how about this? When it seems possible to do so, why not choose to return to hope? And, for those of us who are fortunate enough not to live in the midst of the kinds of horrors that erase hope, why not put an extra emphasis on hope so that we can carry those who feel hopeless forward with us?

Here’s one lesson I learned in seminary that has carried me through the years, both professionally when I served as a minister and personally as I live the same kind of life everyone else does, a life filled with joy, sorrow, and every other emotion in between: Hope is a moving target.

Yes, hope is a moving target. And we can choose to keep aiming for it.

I can no longer remember who coined that phrase for me, but I have found it to be so very true. You get the terrible diagnosis, and you hope for a cure. Your illness is deemed incurable, and you hope for a miracle. A miracle doesn’t seem to be forthcoming, and you hope for a good stretch of time before death inevitably arrives. Time seems to be fading, and you hope to see that one person so that you can mend your relationship with them. Your days seem to be drawing to the close, and you hope for a peaceful death free of pain. At some point, you may even hope for death itself — the ultimate release from pain and suffering.

In other words, human beings often seem to be geared to constantly scan the horizon to find that one ray of hope. Even Eeyore pessimists, the “when-my-ship-comes-in-I’ll-be-at-the-airport” people, usually can find something to hope for.

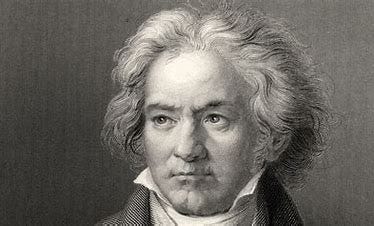

Here’s a story I love. Lugwig von Beethoven finished composing his 9th (and final) symphony 200 years ago, in 1824, three years before he died. You doubtless know at least some of the details of Beethoven’s impossible story. In his late 20s, Beethoven's hearing began to fail. By the time he was 41, he had given up conducting and performing. By the last decade of his life, he was nearly completely deaf — Beethoven, one of the greatest composers of all time. But he continued composing.

That is worth repeating. He continued composing. Even after he was nearly completely deaf. Even though he would never actually hear the fruits of his labors. He continued composing.

Beethoven’s 9th Symphony was premiered in Vienna on May 7, 1824. During the premier, Beethoven shared the stage with the symphony's official director, Michael Umlauf. Beethoven turned the pages of his own score and beat his baton for an orchestra he could not hear. One of the violinists recalled: "Beethoven directed the piece himself; that is, he stood before the lectern and gesticulated furiously. At times he rose, at other times he shrank to the ground, he moved as if he wanted to play all the instruments himself and sing for the whole chorus. All the musicians minded his rhythm alone while playing."

Regardless of how much the musicians “minded his rhythm alone while playing,” the symphony was concluded and the audience burst into wild applause before Beethoven actually finished conducting. Only when contralto Caroline Ungar turned Beethoven around to face the audience did he understand the music had ended to the audience's jubilant acclamation. There were five standing ovations, handkerchiefs and hands raised high in the air and hats lofted airborne so that Beethoven could see the audience's response after writing and conducting a masterpiece he could not hear.

What could be a more accursed affliction for a composer and musician than deafness? In a letter he wrote to his brothers, but never sent, Beethoven recorded his despair and suicidal thoughts, but concluded he must live on for his music. How fortunate for us that he did so.

I was just as child when I first heard Beethoven's story. For the longest time, I used to wonder about the mechanics of it. How could Beethoven compose music when he couldn't even hear? Now, with a faint glimmer of understanding of how music is put together, I can imagine how Beethoven — with his training, his memory of sounds, his understanding of music theory, and his pure genius — could compose, even though deaf. But I still wonder what enabled him to carry on when an impenetrable wall separated him from what he cherished. How did creativity move through him, when despair must have beaten wildly at the door? For me, there is a fierceness in Beethoven's story that helps me to remember that no matter how bad things are there is a way forward.

Beethoven died in 1827 at the age of 56. By all accounts, he endured his share of unhappiness during his lifetime, not the least of which was his steadily worsening deafness. Family dysfunction, abuse, and alcoholism (at least with regard to his father and possibly with regard to himself as well) plagued him. He never seemed to quite find love, although he had hopes that relationships with several different women over the course of his lifetime might deepen into marriage. As his deafness worsened, he had to give up performing — which had been a source of joy and satisfaction, not to mention income — and he withdrew into social isolation. But despite his difficulties, he kept composing.

I do not know what inspired Beethoven’s creativity. Was it fleeting moments of hope, captured as he scanned a somewhat bleak landscape? Did it come from some source no one can truly name or fully understand? I honestly do not know. But I can say definitively that his story gives me hope. In that way, his music continues to offer beauty to our world, and his life story can provide one of those sparks of hope we can harvest. At least that is true for me.

Beethoven never knew the end of his own story, because his music still soars, even today. That's how it is with life: The story is always unfolding. Even our own personal stories keep unfolding after we die. Knowing that gives me hope that my actions may make a difference, even if I don't see it in my lifetime. Whatever good I contribute today may well feed into whatever follows. The same is true for all of us, whether we are great masters like Beethoven or people who simply sing out-of-tune lullabies to the babies in the NICU.

So grant a kindness today, for someday that kindness may multiply. Work for peace today, for someday that peace may become manifest. Cultivate imagination and offer its creativity today, for someday that creativity may inspire someone else. Advocate for freedom and justice today, for freedom and justice await in the distance if only we will move toward them. Love today, for someday love may rise up and embrace our world. Those are seeds we plant so that someday they will achieve their own true growing. The distance ranges far beyond us, but if we move into it with dreams, vision, and hope, we will bestow our greatest gifts upon our world.

Love,

Sylvia

P.S. Just for fun, I offer up the link to this flash mob performing Ode to Joy in Nuremburg, Germany. The music is stunning (as this particular piece always is), and equally stunning, I think, are the faces of the people gathered to play and listen to (and, in some cases, sing along with) the music: Bing Videos

Sources: Beethoven - Symphony No. 9 'choral': description -- Classic Cat

AMEN!!!

I love this so much! And, I'm embarrassed to admit, I knew nothing (nada!) about Beethoven's deafness nor his lifelong efforts to continue his vocation despite it all. Very inspiring, indeed! Thank you for this infusing of hope into my day. It's a very fine sermon!