I am not much of a baseball aficionado, although I have many family members who are. I am pretty much indifferent to the sport unless I can attend a game in person. Who can afford that these days? Not me. I realize that makes me un-American, but not as un-American as many others I can think of. (That is all I will say about the matter . . . here . . . This blog intentionally steers clear of politics to give us a necessary break. But catch me on the street, and you might encounter a different stream of verbiage. Just ask my poor neighbors who, so far, have managed to put up with me.)

But, back to baseball. I do have a favorite team: the Boston Red Sox. Of course, the Boston Red Sox. My favoritism is the result of inheritance, geographical location, and the desire for self-preservation. I think Mainers may love the Sox even more than Bostonians do.

When I say the Red Sox are my favorite, that just means I may or may not know (chances are the latter) how they are doing and whether or not they made the playoffs or the World Series. I can’t watch them on television because I don’t own a television set. These days of streaming things might make it possible to catch games on my husband’s computer with the larger screen or my computer with the smaller screen. I could listen on the radio, too, all the while thinking of my brother who has been known to say, “The colors come in better on the radio.” But, eh? It’s just not me.

So, when I woke up Wednesday morning to the news that the famous Willie Mays had died, my first thought was, “You mean he was still alive?” My second thought was (and I am embarrassed to admit this), “He was baseball, right?”

I know. Un-American. I’m not proud of it, but, at this late stage, I am unlikely to change. Besides, I figure my moral lapses with regard to baseball in general and the Red Sox in particular are more than balanced by the unadulterated loyalty of certain members of my family. I am counting on their faithfulness to get me into heaven. I figure they will just reach out a hand and pull me up into the clouds.

I’m looking at you, Daddy.

My father was born just outside of Boston in the spring of 1918, a few months before the Boston Red Sox won the World Series. A tiny baby, he couldn’t appreciate that sweet victory, but he harbored a deep love for the Red Sox for his entire life. He always lived in hope that this might be their year! Most of the time, he watched the games on television. But, when we were kids, he took us to the ballgame at Fenway Park once a year. That was back in the days when you didn’t need a hefty trust fund to be able to afford tickets.

One time, when I was quite little, our family of five lined up at Park Street Station for the Green Line train over to Fenway Park. The trolley arrived, its doors opened . . . and then closed before all of us could climb aboard by squishing and squashing our bodies into the multitudes of people headed for the game. Recollections about the event differ among us siblings, but here’s how I remember it: My father and oldest brother got onto the trolley car. My mother, middle brother, and I were left standing on the platform. The trolley rumbled away without us, carrying off the one member of the family — my father — who knew how to navigate the Boston subway system. Also, he had the tickets to the game in his pocket.

There my mother was, stranded in Park Street Station with two little kids in tow. Not only was she a novice at figuring out how to get to where we were going, but she also suffered from claustrophobia. If you have ever ridden on a super-crowded Green Line train heading to Fenway Park, you can imagine how challenged and stressed she must have felt. It was one of those “keep calm and carry on” moments parents endure every so often, when, regardless of inner anxieties or fears, they have to exude confidence and calm so that their children don’t freak out. I cannot remember if the Sox won that day, but I do remember the family was reunited once the next trolley deposited us laggers at the Fenway stop. And we were all left with a story to tell.

When the Sox played in the World Series in 1967, Daddy managed to get a ticket to one of the games — a huge thrill! The Sox lost that series. My father’s love for the team continued unabated. When he died in 2000, he had lived nearly 82 years without ever witnessing his beloved team win the World Series. He suffered with them through some pretty terrible years. And he got excited for them in the good years, when the glorious title seemed within reach.

Loyalty demands riding the tide that shifts between good fortune and ill. Sometimes it demands going an entire lifetime without seeing one’s dream come true. Remember, even Moses did not reach the Promised Land with his people. Remember Martin Luther King’s last speech, just before he was assassinated, when he said, famously,

“We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop . . . I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

In 2004, the World Series when the Red Sox finally broke “the curse of the Bambino,” my nephew, who was living in St. Louis at the time, got tickets to one of the games — the winning game, as it turned out to be. His dad (my oldest brother) flew in from Colorado to help cheer our team on. My middle brother Express-mailed my father’s Red Sox cap to St. Louis so that our nephew and oldest brother could wear it at the game. When the Cardinals made their final out, sending the long-coveted trophy north to Boston, Daddy was there “in hat” as well as in spirit.

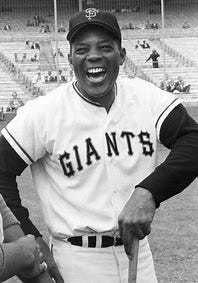

Now I know Willie Mays wasn’t one of the Red Sox. (I know this because, when I googled his image, he was wearing a shirt that said, “Giants.” That was a pretty big clue.) But one can be a Red Sox fan and still admire the legend that Mays was. My brother told me that when he was at Fenway Park for a game some 20 or 30 years ago, they announced that a very special guest was there that day: Willie Mays. The crowd responded with a standing ovation. If my father could have been at Fenway Park that day, he would have risen to his feet in tribute and admiration, I am sure.

Daddy was philosophical about things. Sure, he would have loved to have seen the Red Sox win another championship in his lifetime. At the same time, he understood championships were the result of hard work and even, to some extent, luck. He certainly knew victory could be elusive. In his own life, he accepted that his own best efforts were sometimes rewarded and sometimes not. He used to say that as long as he knew he had done the best he could, he could sleep well at night.

Willie Mays, too, would have understood hard work. He would have known victory could be elusive. He would have understood the importance of doing one’s best, despite obstacles. And, surely, he would have understood obstacles all too well. Today he is celebrated not only for his extraordinary talent, but also for the role he played in helping to open the doors to black players in major league baseball. Surely, he was well aware of the racist history that had kept extraordinary black baseball players out of the major leagues. He also knew that was just the tip of the iceberg where it came to oppression. Wednesday’s tribute in the New York Times included this eye-popping paragraph:

“President Barack Obama took Mays with him on his flight to the 2009 All-Star Game in St. Louis, telling him that if it hadn’t been for the changes in attitude that African-American figures like Mays and Jackie Robinson fostered, ‘I’m not sure that I would get elected to the White House.’”

It strikes me that, whoever we are, we are here because of the sacrifices of countless others, going way back in time — an estimated 350,000 generations. Every generation dies away, leaving those behind to continue on. In that sense, our work is never finished. We have our chance to make an impact, but we may die before we see the results — just as my father died before the Red Sox won the World Series again.

In 1853, a Boston (yes, Boston again!) minister, the Rev. Theodore Parker, spoke some words that have become famous in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s adaptation of them:

“I do not pretend to understand the moral universe, the arc is a long one, my eye reaches but little ways. I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by the experience of sight; I can divine it by conscience. But from what I see I am sure it bends towards justice.”

So we do the work we are called to do, hoping our efforts will help bend that arc, even if we do not live long enough to see the halcyon results. Sometimes a certain amount of faith is required to be confident change will come, even if that change is years, decades, lifetimes, or even longer in the making. That’s the kind of faith Red Sox fans like my father had to have for most of the 20th century. That’s the kind of faith Willie Mays must have mustered at the start of his career, when black baseball players were held back. That’s the kind of confidence untold numbers of now-nameless people must have had to do their part to propel the world forward toward increased justice and peace.

Maybe there’s a lesson there for us. Hold onto your hat and keep playing, because the game isn’t over yet. Do the best you can. Keep calm and carry on.

Love,

Sylvia

Notes: Remembering Willie Mays as Both Untouchable and Human - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

https://quoteinvestigator.com/2012/11/15/arc-of-universe/

Comparing the loyalty of Red Socks fans to our faith in Justice. Sparked by the death of Willie Mays and memories of a Fenway Trolly ride. You’re something, Sylvie! But then I knew this from your very first story/ sermon about ducks…. Can’t recall the plot, but my admiration for your natural way of sharing the yarn is unforgettable.

Thank you.

My experience with baseball was a parallel to yours, minus the trolley ride! Ted Williams was worshipped by my father and brothers.

I love the way you brought it to today, with a little guidance about how to get through our troublesome world. Mary